Thirty years ago cave explorer Grant Gartrell and palaeontologist Rod Wells of Flinders University were exploring Victoria Cave in Naracoorte hoping to find fossil bones when they broke through to a concealed passageway. In the unexplored caverns beyond they discovered the largest, most diverse and best preserved Pleistocene vertebrate fossil assemblage in Australia in what is now known as the Fossil Chamber. Because of the extraordinary richness and potential of these fossil deposits, the Naracoorte Caves were declared a World Heritage site in 1994. Recognised as one of the world's most important fossil sites, the caves offer experiences for all ages. These caves were main attraction of this trip to the Limestone Coast.

The limestone of the area was formed from coral and marine creatures 200 million years ago and again 20 million years ago when the land was below sea level. Ground water since then has dissolved and eroded some of the limestone, creating the caves. The caves, such as the Victoria Fossil Cave and Blanche Cave, are often not far below ground, and holes open up creating traps for the unwary. This is the source of the remarkable collection of fossils. Mammals and other land creatures have fallen into open caves and been unable to escape. The fossil record has been preserved in strata formed from eroded topsoil washed and blown in. In some places, the fossil-bearing silt is up to 20 metres thick. Some of these areas are being preserved for future research when better methods of dating and reconstructing fossil records may have been found. These fossil traps are especially significant for tracing Australian megafauna.

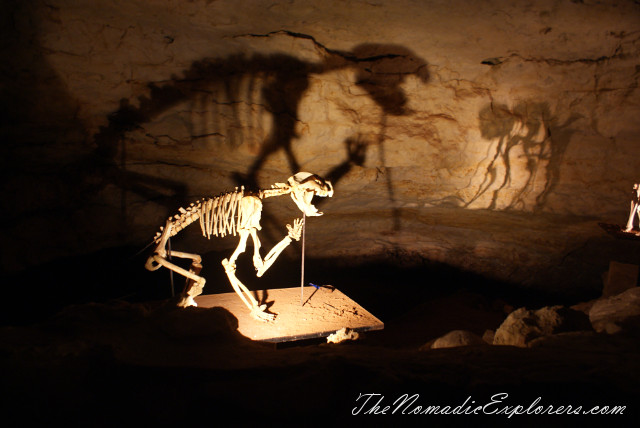

Skeleton of a marsupial lion (Thylacoleo carnifex) in the Victoria Fossil Cave

During the last twenty years approximately 138 cubic metres of sediment and bones have been removed from three pits within the Fossil Chamber representing approx. 4% of the estimated 5000 tonnes of bone laden sediments. This comparatively small volume has resulted in 5200 museum catalogued specimens, these being but a small fraction of the total fossil material so far prepared. Only a small representative sample has been removed from the surface in the Ossuaries for dating, otherwise these chambers remain in near pristine condition.

According to the National Park website, four caves are open to the public, tours performed daily. We went to the Victoria Fossil Cave tour, which is one of the best showcases of the World heritage values of the park.

From the 3-4 m deep Fossil Bed, tens of thousands of specimens representing at least 93 vertebrate species have been recovered. These include superbly preserved examples of the Australian Ice-Age Megafauna (giant, extinct mammals, birds and reptiles) as well as a host of essentially modern species such as the Tasmanian Devil and Thylacine, wallabies, possums, bettongs, mice, bats, snakes, parrots, turtles, lizards and frogs. The fossil material includes complete postcranial remains (many of which are partially articulated) and skulls so well-preserved that even the most delicate bones (e.g. the nasal turbinals) are still intact.

We also went to Wet Cave, which is the only cave you can visit without a guide. Lights in the cave are activated by motion sensors so you can explore at your leisure. The robust columns and stalactites offer a wonderful contrast to the delicate formations in Alexandra Cave. About 20 steps lead down into the cave and it is suitable for all ages.

Wet Cave:

I wish we could spend more time there and visit one more cave, but it was a last day of your journey and we had to go back home. In the next posts I will tell you what we have seen during our way to Melbourne.